West Africa: EU Sahel Envoy Warns Liberia On Regional Spillover Risks

The European Union’s top envoy for the Sahel warned Tuesday that Liberia cannot afford to ignore the region’s spiraling instability, urging tighter border controls, vigilance against disinformation and sustained engagement as Monrovia prepares to take a seat on the U.N. Security Council.

“Liberia is not the Sahel, and it is not immediately affected by Sahelian dynamics,” João Gomes Cravinho, the EU Special Representative for the Sahel, told reporters in Monrovia. “But the truth is the whole region is destabilized, and this can in the near or medium term have very negative consequences for Liberia.”

Cravinho, a former Portuguese foreign minister appointed EU envoy in December 2024, met with Foreign Minister Sara Beysolow Nyanti; Liberia’s National Security Council chaired by the justice minister and including the national security adviser, the army chief of staff, the heads of security agencies and immigration, and the deputy defense minister as well as civil society groups and Liberia National Police Inspector General. He said his mission was to hear Liberian perspectives on the Sahel, assess areas for EU-Liberia cooperation and understand the country’s own security pressures.

“The program began with a meeting with the foreign minister,” he said. “Then I had a meeting with the National Security Council … Today I engaged with a cross-section of civil society about the Sahel and also visited police headquarters, where the Inspector General briefed me on challenges in regional police cooperation.”

Border porosity, Burkinabè arrivals and land tensions

Cravinho said his interlocutors repeatedly flagged the “porosity of national borders–land borders, but also the territorial waters and points of access, particularly the airport and ports.” That vulnerability, he added, is especially risky “in an age where there is increased trafficking of all sorts, including human trafficking.”

Asked about the recent arrival of Burkinabè nationals into Liberia, the envoy said authorities had briefed him on the phenomenon and its drivers. “You link it to climate change. I think, yes, climate change is a factor,” he said. “But also insecurity, generalized insecurity in Burkina Faso as a result of terrorist activities in many different parts of the territory, has led to this influx.”

Most of those leaving Burkina Faso have gone to Côte d’Ivoire, he noted, and “a small portion, it appears, have been making their way over to the territory of Liberia.” The immediate risk, he suggested, was less about militant infiltration than about pressure on land.

“I was quite struck by a comment made by the Inspector General of Police,” Cravinho said. “As far as I understand it, the assessment at the moment is that these Burkinabè citizens are above all looking for lands and the opportunity to farm … But the Inspector General said disputes over land are the most important trigger of violence in Liberia.”

Cravinho noted that “there is no evidence at the moment” that terrorists are crossing into Liberia in the current wave of arrivals. Yet, he cautioned, the influx “doesn’t mean [it] is problem-free because of all of the issues related to land disputes,” dynamics made “more acute because of climate change” and shifting “geographies of arable lands in this region.”

A polycrisis next door–and why it matters to Liberia

Pressed on how the Sahel reached its present state, Cravinho called it “a polycrisis … a concurrence of various different types of crises.” He cited “very grave” socioeconomic deprivation; a youth bulge with “very few options in terms of job prospects,” pushing some toward “very risky, very dangerous migratory paths” or “jihadist groups”; decades of governance failures with colonial-era roots; climate-driven conflict between herders and farmers “in circumstances in which literally the ground under their feet is changing”; and “global geopolitics,” including “the intervention of Russia,” which “has not helped to stabilize matters.”

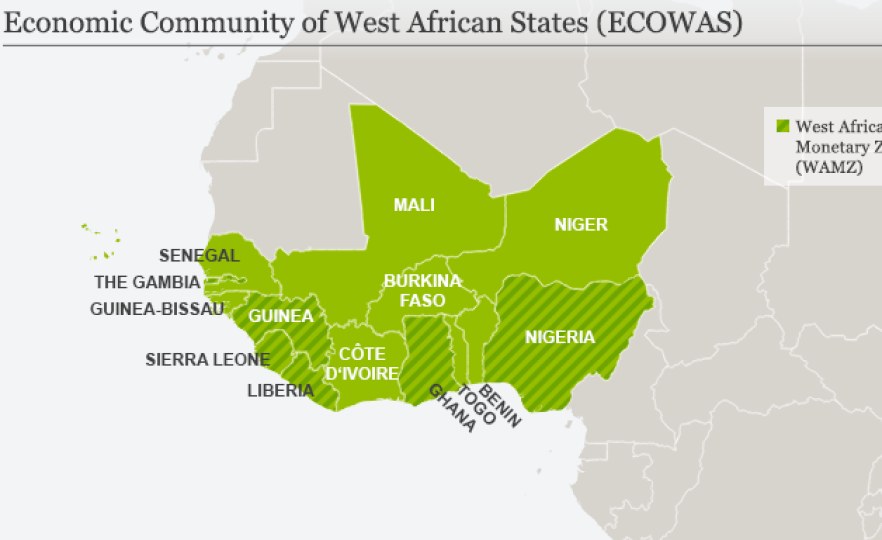

The consequences, he said, now extend beyond Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger into “northern Togo, northern Benin, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana.” Liberia, buffered by neighbors, is not currently experiencing the same spillovers. “But certainly it doesn’t help Liberia’s current circumstances that not too far away you have such deep crises with populations on the move because they cannot stay where they are,” he said. “It is necessary for us to work closely with Liberia to ensure that the situation in the Sahel stabilizes, because otherwise the consequences will be felt not just in Liberia–they will be felt also in Europe.”

From punitive posture to engagement

Cravinho signaled that Brussels is shifting its Sahel playbook after years of coups and ruptured ties. “We now have developed what we call our renewed approach,” he said. “We don’t have a punitive approach. We have an approach which agrees to disagree in some respects … but we also believe we have to be able to work together on issues where we have an interest and the populations of those countries also have an interest.”

He said the EU will not legitimize military seizures of power. “We don’t agree with regimes that have reached power illegitimately,” he said. “But there are a number of issues on which we think it is important to work with those who are in power in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger in mutual interests.”

Direct cooperation with the juntas’ armies is off the table, he added, noting that Mali and, to a lesser extent, Burkina Faso “have chosen to partner with Russia in the fight against terrorism.” That decision, he argued, “has not been very successful because the situation has got worse and not better militarily.”

Even so, the EU has kept civilian security missions in place where possible. “In Mali … we have maintained the presence of a civilian security cooperation mission,” he said, referring to EUCAP Sahel Mali. The mission “does work with training of police, training border guards,” and “agents of rule of law, such as judges,” to strengthen capacity. Beyond security, he pointed to development and humanitarian work, including support along the Ouagadougou-Abidjan corridor, “a lifeline for the country,” aimed at helping farm communities “get their produce to market” despite insecurity.

“It is a mistake now well recognized to imagine that the security situation in the Sahel can be solved by military means alone,” Cravinho said. “You need an approach that is holistic.”

ECOWAS, the AES split and Liberia’s diplomatic role

Cravinho acknowledged that the departure of Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger from ECOWAS in favor of their Alliance of Sahel States “somewhat debilitated” the regional bloc as a Sahel partner. But he urged patience and continued dialogue.

“After the more emotional period, which is the period of the breakup, countries will realize that they have to work together,” he said. “We’re already seeing signals that AES countries … want to work with ECOWAS countries on challenges they face.”

Liberia, he suggested, could help bridge divides, especially as a non-permanent member of the U.N. Security Council beginning in January. “One aspect the foreign minister underlined to me is that the centerpiece of Liberia’s program for the U.N. Security Council is an emphasis upon Women, Peace and Security and Youth, Peace and Security,” he said. “Liberia’s own history … is interesting as an example of a country in deep conflict which managed to climb out of that conflict with a very important contribution from women. This entitles Liberia … to bring that experience to the Security Council table.”

“The Sahel is mostly young people–70% of the population 25 or under,” he added. “Any program for the Sahel that does not contemplate the central role for young people is unlikely to succeed.”

Cravinho said the EU intends to keep close contact with Liberia’s Security Council team. “We arranged with the foreign minister that we would continue to consult in New York,” he said, while the EU Delegation in Monrovia will maintain day-to-day coordination.

Migration, Europe and working at the source

On migration to Europe, Cravinho said EU policy has matured beyond “simplistic thinking.” “Perhaps some years ago, some politicians in Europe thought that, you know, you build a wall in the middle of the Mediterranean, and that’s it,” he said. “Fortunately [that] is not at all prevalent nowadays.”

“To have control over migratory flows, it is necessary to work in the countries of origin,” he said. “In the Sahel, the migratory flows to Europe are coming mainly from Mali … Burkina Faso has enormous outflow, but not to Europe … [And] in Niger, there is not a great migratory tradition.”

With insecurity and bleak prospects, he warned, “this region is going to have a big outflow of people unless we can work … to create better futures.”

Disinformation as a democratic threat

He also highlighted the corrosive impact of disinformation, avoiding direct commentary on Liberia but stressing the global stakes. “We’re seeing the results of disinformation having a destructuring impact on societies around the world,” he said. “This is a threat to democracies … aimed at destabilizing and weakening democratic structures and promoting non-democratic forms of government.”

He urged skepticism and stronger media literacy. “It’s important for us when we look at social media to be suspicious,” he told journalists. “Good journalists are suspicious … That’s the kind of mediation that allows you to be credible.”

The EU, he said, supports independent media and fact-checking across the region. “When you don’t have a source of trusted information, this is when trust begins to break down between citizens and institutions,” he warned. The EU Delegation in Monrovia added that it has backed capacity-building, data-protection training and election-period fact-checking with Liberian

By Liberian Investigator.