Africa Beyond Aid

When America’s first felon announced a funding freeze of US humanitarian aid and ‘development assistance’ for 90 days, little did he know that he would ignite a reckoning not seen since independence movements began across much of Africa, Asia and Latin America.

Rather than likening aid suspension to the apocalypse, we should instead embrace it as a catalyst for 21st century decolonization.

For those of us who understand that structural barriers make achieving socio-economic transformation in the so-called ‘Global South’ difficult, nigh impossible, Washington’s exemption of military aid to Israel appeared rather self-serving and spiteful. But it also exposed the disingenuousness of an aid system that lacks transparency, operates as a tool of neocolonial control, and breeds dependency.

The glaring contradictions inherent in America’s executive (dis)order appear to have galvanized people with largely divergent perspectives about the promise and pitfalls of aid, including those Nilima Gulrajani calls aid radicals (who believe in abolishing an oppressively colonial aid system), aid reformists (who believe in improving and effectively managing aid) and aid realists (who fall somewhere in the middle).

While most acknowledge the pivotal role aid has played in saving lives and keeping afloat crumbling health and education systems, there are visceral debates ongoing about its (un)sustainability.

He who feeds you, controls you

When Burkina Faso’s revolutionary leader Thomas Sankara famously said, “he who feeds you, controls you”, he was demystifying a multi-billion-dollar industry whose modus operandi is to entrench geopolitical hierarchies of power and sustain global economic inequalities.

The international aid system was established after World War II to rebuild and reconstruct parts of Europe and Asia; it was never intended to develop Africa or other parts of the colonized world. As former colonizers used aid to maintain influence over a decolonizing ‘South’, nationalists in Africa, Asia and Latin America advocated in the 1970s and 1980s for a new international economic order that would render aid obsolete.

Since then, aid has been wielded as a tool of soft power to advance the interests of foreign financiers (so-called ‘donors’) largely in the West and their proxies in international financial institutions like the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF), multilateral organizations such as the United Nations, and international NGOs such as Save the Children and Oxfam.

Aid is clearly strategic, rather than altruistic.

For example, the US agency for international development (USAID) was established by President John F. Kennedy in 1961 to fight the spread of communism, with one American diplomat recently admitting in a live broadcast that “US aid is not charity.

It is a tool for advancing the interests of the United States”. Few aid industry zealots care to concede that the funding freeze disproportionately impacts American companies, contractors and NGOs which absorb 31% of financing after 12% overhead/admin is skimmed off. The lion’s share of USAID financing, 46%, is channelled through multilateral implementing partners such as the UN and World Bank, with only 11% going directly to foreign institutions, including governments, companies and NGOs.

Ilhan Kapoor calls this ‘fraudulent kindliness’ and he is absolutely right.

Seek ye first the economic kingdom

Countries in the ‘South’, including in Africa, have sobered to the reality that aid can never bring about structural transformation. When Ghana’s first post-independence president Kwame Nkrumah admonished countries across the continent to “seek ye first the economic kingdom”, he understood that political sovereignty without economic independence was useless.

Other African leaders followed in succession, championing self-reliance as a counterpoint to the burgeoning aid system.

Tanzania’s Julius Nyerere adopted ‘ujamaa’ (‘familyhood’ in Swahili) as the bedrock of his economic and social policies between 1964 and 1985. He focused on ‘villagization’ to reverse colonial-era rural to urban migration, collective agriculture and communal ownership of land to achieve food security, nationalization of productive enterprises to ensure value addition, and public investment in social services to improve health and education outcomes.

Kenneth Kaunda adopted ‘Zambian humanism’ as a basic needs approach to achieving socio-economic transformation. The goals of his development plans between 1964 and 1970 included balanced and inclusive growth, public sector development of economic and social infrastructure, and delinking from the settler-dominated countries of Southern Africa.

And Thomas Sankara attained astonishing development dividends during his very short time in office from 1983 to 1987. Under Sankara’s stewardship, Burkina Faso reduced infant mortality and increased literacy rates through investments in health and education, respectively. The country also achieved food sufficiency by redistributing land to rural peasants, amongst other reforms.

Like Nkrumah, Sankara, Kaunda and Nyerere understood intuitively that Africa must develop on its own terms with its own resources. Sankara in particular eschewed aid, advocating instead for the cancellation of odious debts. He did so amidst IMF-backed structural adjustment policies from the 1980s onwards that gutted government bureaucracies across Africa, Asia and Latin America while entrenching market logics into policymaking processes and intensifying disparities between the poor and prosperous.

Beyond aid

Although current African leaders generally lack the chutzpah of Sankara and moral acuity of Nkrumah, some appear to have embraced their spirit of defiance. This was evident during February’s African Union (AU) Summit in which heads of state strategized about alternatives to aid.

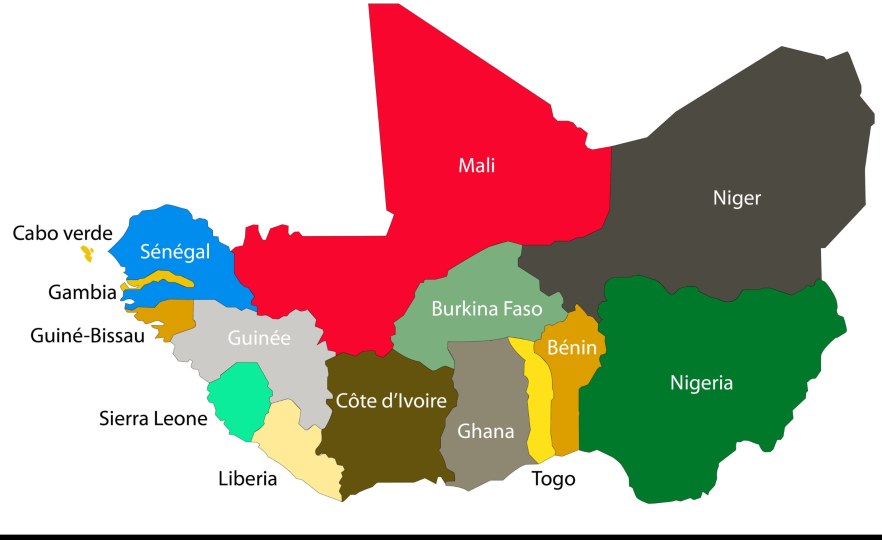

Reparations for colonialism and transatlantic slavery featured prominently in deliberations. So too did debt restructuring and boosting intra-Africa trade, which accounts for merely 18% of overall trade with the continent, as part of the AU’s flagship African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). Importantly missing from the discussions, however, were strategies for curbing corruption and adding value to basic commodities.

Having recognized Africa’s unequal incorporation into global capitalism under unfavorable terms, leaders across the continent are challenging the structural inequities that create conditions for aid in the first place.

The African Development Bank has advocated for an autonomous African credit rating agency to counter biases upheld by ‘Big Three’ global agencies Standard & Poor’s, Moody’s and Fitch.

Nigeria has pushed for changes to international tax treaties that restrict the rights of ‘Southern countries’, with Africa in particular losing nearly US$90 billion annually from illicit financial flows.

Calls for swift reforms within the World Trade Organization and UN have reached fever pitch, with countries like Ethiopia and Egypt ditching Western dictates in favor of BRICS membership.

So many across Africa, and the wider ‘Global South’, are embracing a ‘beyond aid’ agenda which promotes significantly reducing dependence on aid over time while diversifying sources of revenue and financing. ‘Beyond Aid’ acknowledges that aid is not a viable development strategy, and that inclusive economic growth enables sovereignty.

As a case in point, projections indicate that 28 countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America, with total populations of two billion, will no longer be eligible for ‘overseas development assistance’ (ODA) by 2030 because of their expanding national incomes. Similarly, aid budgets typically fall below the UN’s recommended 0.7% of gross national income (GNI), with countries like the UK, France and Germany cutting already dwindling ODA to serve increasingly narrow self-interests.

Rather than espousing the abolition of aid, proponents of ‘Beyond Aid’ take a more measured approach to reform which could unlock Africa’s capacity and autonomy to develop.

In my country Liberia, where foreign aid accounts for about 20% of gross domestic product (GDP), changing dynamics within our imaginary ‘special relationship’ with the United States are turbocharging long-overdue reforms. Policymakers are now compelled to do what they should have been doing all along: slashing the national budget to remove waste, improving revenue collection through taxation, reviewing and renegotiating concession agreements, investing in agriculture and food security, building infrastructure and exploring renewable energy.

These shifts in practice were the hallmarks of my July 2024 Independence Day national oration in which I urged compatriots to build back better and differently. Other policy changes I championed, which could be accelerated to fill gaps in financing, include establishing a National Anti-Corruption Court to restitute stolen funds, forming new strategic development partnerships within Africa and further afield, implementing sustainable debt financing, diversifying domestic resource mobilization through investments in the creative industries, and leveraging remittances from Liberians abroad which account for 20% of GDP.

I was particularly heartened when our minister of finance and development planning responded to Washington’s aid freeze by stating emphatically: “Liberia is a resilient country. We have survived the devastating 14-year civil war, the Ebola epidemic, and the COVID-19 pandemic…With strategic adjustments and collective effort, we will navigate these challenges and continue on our path to growth and stability.”

Indeed, Africa must and will survive beyond aid.

By Liberian Observer.