West Africa: Can Realpolitik Drive Renewed Regional Cooperation in West Africa?

The AES-ECOWAS split has sparked pragmatic cooperation based on strategic interests between neighbouring countries.

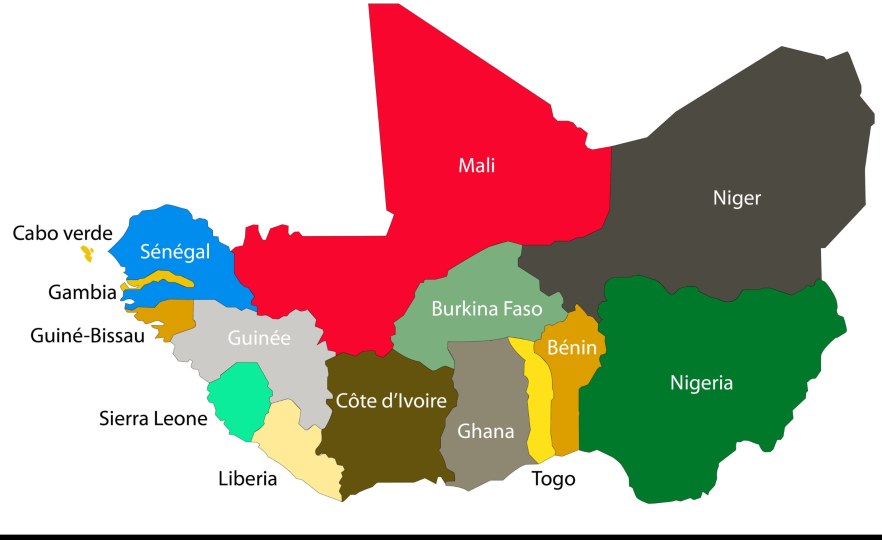

Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger’s withdrawal from the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) became official in January. A month earlier, ECOWAS decided on a six-month grace period to define the terms of separation and a framework for engagement. But nearly four months on, negotiations have not begun.

ECOWAS is currently focused on two other milestones: its 50th anniversary celebrations and the upcoming Special Summit on the Future of Regional Integration in West Africa.

The regional organisation remains hopeful that Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger – making up the Alliance of Sahel States (AES) – will reconsider their departure. On the sidelines of the April ECOWAS Council of Ministers Extraordinary Session in Accra, Ghana launched a new mediation initiative aimed at reintegrating the three states.

But this seems unlikely in the short term. Beyond ECOWAS’ missteps in handling military coups, the three military regimes have adopted domestic narratives opposing both ECOWAS and the West.

Meanwhile, ECOWAS cannot readmit these countries without bending its principles on democracy and governance. The juntas have rejected any compromises on their transition timelines – the main political gain from their ‘immediate effect’ withdrawal. Burkina Faso and Niger have embarked on five-year transitions, and Mali seems set to follow suit, despite internal political risks.

Nonetheless, economic integration remains a shared interest. In the short term, the free movement of goods, people and capital will continue between AES members and countries such as Benin, Togo, Senegal, Côte d’Ivoire and Guinea-Bissau. These eight countries are members of the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU), whose treaty guarantees these principles.

So future negotiations will focus on the remaining seven ECOWAS countries: Cape Verde, Ghana, Guinea, Liberia, Nigeria, Sierra Leone and The Gambia. A potential bargaining tool is the AES’ new 0.5% customs duty exempting WAEMU member states. It is especially relevant to Nigeria and to a lesser extent, Ghana, given their trade influence.

Meanwhile, the withdrawal has created administrative and financial challenges. In February it was reported that ECOWAS had dismissed 135 employees hailing from AES countries, but is now considering a phased separation to mitigate staffing shortages.

Also unresolved are the withdrawing states’ statutory financial contributions to ECOWAS and the costs of projects that the bloc continued implementing in their territories between their January 2024 withdrawal announcement and exit in January 2025. ECOWAS regulations stipulate that they should have maintained their financial commitments during this time.

The split also complicates the financing and repayment of numerous cross-border infrastructure projects spanning the ECOWAS and AES zones. These include regional corridors funded by donor consortia including the ECOWAS Bank for Investment and Development. This could lead to complex and lengthy negotiations.

Yet, the evolving regional landscape may facilitate progress. Among ECOWAS countries, the once-unified hardline stance has softened. Senegal’s new President Bassirou Diomaye Faye has introduced a more pragmatic approach towards the AES countries.

Nigeria has moderated its position towards Niger, dispatching its foreign minister to Niamey in April. Benin’s President Patrice Talon has acknowledged errors in handling the Nigerien coup, while Côte d’Ivoire’s Alassane Ouattara – eyeing a fourth term – has toned down his rhetoric.

In Guinea-Bissau, President Umaro Sissoco Embaló expelled a joint ECOWAS-United Nations mission seeking political consensus ahead of the country’s November 2025 elections, further weakening ECOWAS’ stance on governance.

The most pivotal shift occurred in Ghana, where President John Dramani Mahama was elected in December 2024. Mahama swiftly re-engaged with the AES countries, reshaping Ghana’s regional diplomacy.

These political shifts diminish ECOWAS’ ability to present a unified front. At its April session, the ECOWAS Council of Ministers stressed the need to ‘adopt a collective approach to negotiations as a regional bloc.’ On this point, the AES seems better prepared. In January, its members harmonised their positions on the withdrawal process and adopted a joint negotiation strategy.

The new configuration among ECOWAS members has rebalanced the political power dynamic, creating a window for dialogue. Nevertheless, the prospect of a comprehensive ECOWAS-AES framework – spanning economic and security domains – remains remote in the short term.

Should formal talks falter, the prevailing political momentum may nonetheless yield a new regional compromise grounded in realpolitik.

Mahama referred to the AES as ‘an irreversible reality’ during his January diplomatic tour of the Sahel. His appointment of a former military officer with counter-terrorism expertise as Special Envoy to the AES reflects Ghana’s interest in fostering security cooperation.

The move also enhances the competition between Ghana and Togo for AES business. Niger, Mali and Burkina Faso are landlocked and need access to these two countries’ ports for trade. Similarly, Togo’s overtures towards the AES appear motivated by commercial interest and political preservation, as the relationship could discourage ECOWAS from scrutinising Togo’s domestic affairs.

A similar realism underpinned Nigerian Foreign Minister Yusuf Tuggar’s visit to Niamey. The engagement was a step towards normalising his country’s relationship with Niger, driven by shared strategic, trade and security interests.

In February, Senegal and Mali launched joint counter-terrorism patrols in the Kayes region following a visit by Senegal’s defence minister to Bamako. In May, Togo participated in joint military exercises with AES members and Chad.

Without an institutional security cooperation agreement, this model of ad hoc bilateral cooperation between neighbouring states seems a pragmatic response to urgent transnational security needs.

Côte d’Ivoire is willing to cooperate with Burkina Faso in border areas, and Benin blamed a lack of cooperation with Sahelian neighbours for January and April’s deadly terror attacks – implicitly signalling its readiness to collaborate. In both cases, diplomatic mediation is necessary, and given its renewed ties with the AES, Ghana could lead this initiative.

The Conseil de l’Entente comprises Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Niger, Togo (and Mali as an observer) and could also serve as an informal cooperation framework. It has a low political profile, could host sensitive discussions and provide a parallel framework on security issues.

In July, Nigeria hands over the ECOWAS rotating presidency. Ghana and Senegal – both adopting more moderate and constructive positions on the AES states – could lead the organisation during the negotiation phase and drive political momentum for deeper reforms.

By ISS.